A document kept for 166 years by the courts has revealed an episode that represents the struggle for rights and freedom during the period of slavery in Empire Brazil. Paula, an elderly woman in poor health, obtained a letter of freedom 30 years before the Golden Law, which abolished slavery in 1888. She lived in one of the first settlements in the former north of the state of Goiás, which became Tocantins.

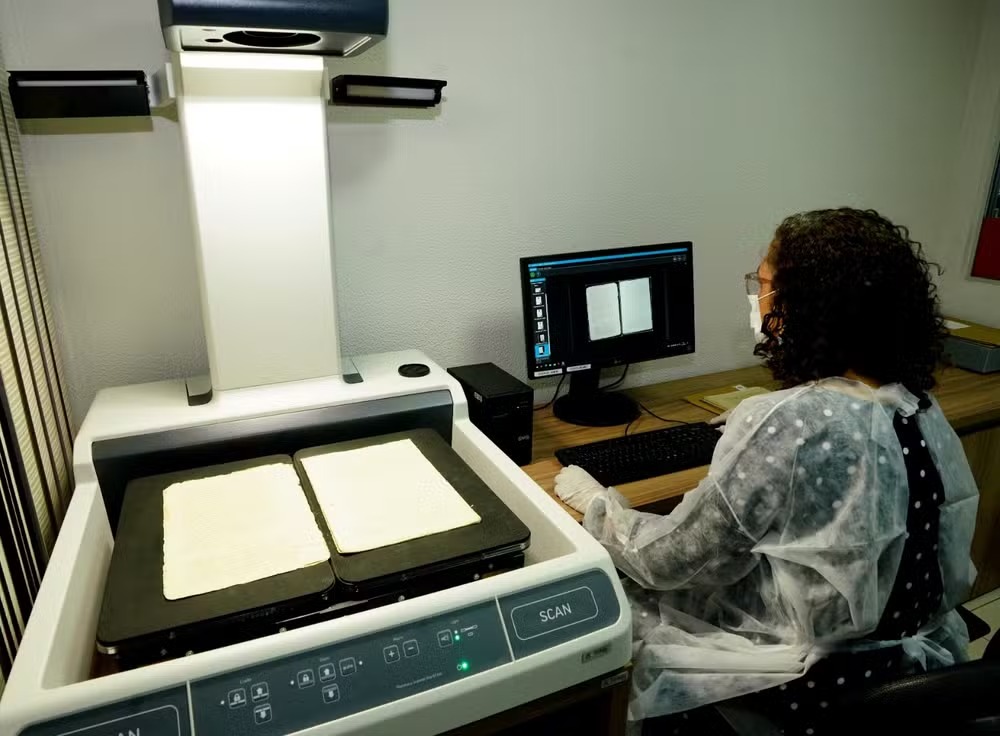

The historic document was released by the Superior School of the Judges of the State of Tocantins (Esmat) on the National Black Awareness Day, celebrated on November 20th. The petitions requesting the freedom of the woman were digitized using state-of-the-art equipment designed to preserve historical documents.

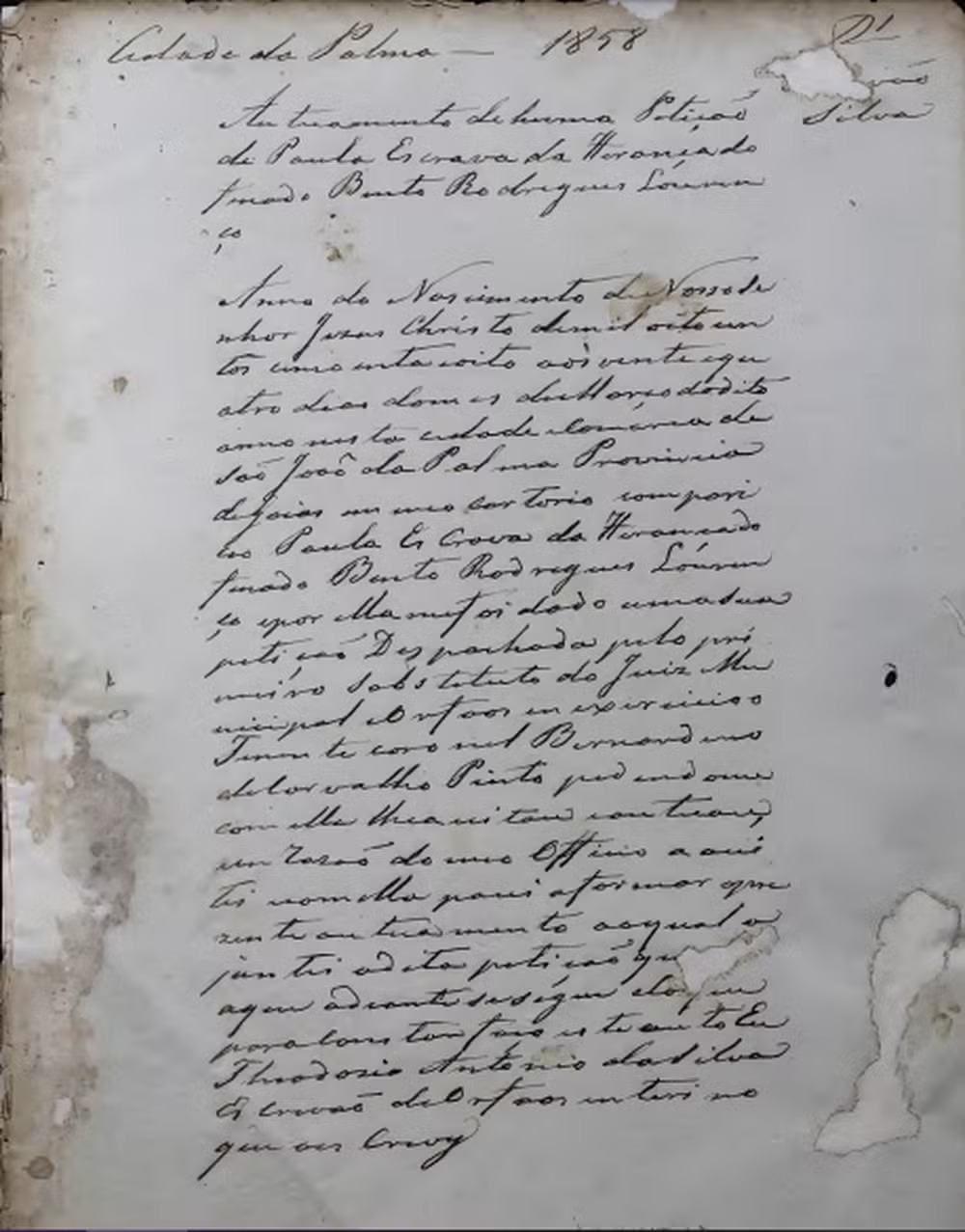

The date of the request for freedom is March 24th, 1858 and because it was handwritten, some details have been lost over time and were ineligible. However, it is possible to understand the context in which the woman obtained her freedom in the district of São João da Palma, now Paranã.

For Justice Marco Villas Boas, General Director of Esmat, making the contents of the document available, as well as its transcription, reveals the Judiciary of the state of Tocantins concern to promote access to information and the duty to remember the enslaved populations who inhabited the territory that is now the state of Tocantins.

“Preserving documentary memory is essential for building the history and identity of a nation. Every day, we delve deeper into the process of the identity of the state of Tocantins without ever ceasing to search for our origins, our references. These documents allow us to revisit the past, shed light on injustices and rewrite history in a new light,” he said.

Inheritance

As difficult as it is to think about this condition of life in the face of the anti-racist struggle of the 21st century, Paula was left as an inheritance to the children of Bento Rodrigues Lourenço, her owner. After a lifetime of being considered 'property', she went to a notary office in the district to apply for her freedom.

In the middle of 1858, there was an abolitionist movement and the Eusébio de Queirós Law of 1850, which banned the slave trade from Africa to Brazil, was in force. The Golden Law was only signed by Princess Isabel in 1888.

The petition from the slave girl was dispatched by the first substitute for the acting Municipal and Orphans Judge - as the position was called at the time - Lieutenant Colonel Bernardino de Carvalho Pinto and passed on to the clerk, Theodozio Antonio da Silva.

In one of the documents addressed to the so-called Judge of Orphans, the general curator of the Court, Antonio Ribeiro da Fonseca, informed that Paula was part of the inventory of Bento Rodrigues and that she - called the petitioner - was valued at 60,000 réis.

He also stated that the heirs were not opposed of giving Paula her freedom.

“If there is no doubt, please accept the amount for which the petitioner was assessed to be paid into the coffers and order VS [your lordship] to issue her letter of release before proceeding with the auction ordered by VS [your lordship] and signed [...] For VS [your lordship] Serving to grant the petitioner with correct justice,” reads the excerpt.

In another request to the judge of orphans, the curator interceded for Paula, stating that she had served the former owner for years and because of “her advanced age and visible illness”, and asked the Court to accept payment of the “assessment for her freedom”.

Freedom on payment

“On the twenty-fourth day of March, one thousand eight hundred and fifty-eight,” as it was written by hand by the actors of the judiciary in Empire Brazil, the slave Paula was freed, upon payment of 60,000 réis.

“[...] the sum of sixty thousand réis for which the petitioner Paula was valued, to be divided among those interested in the inheritance; if the petitioner is granted a letter of freedom and has paid the costs,” said the sentence of the acting judge of orphans, Lieutenant-Colonel Bernardino de Carvalho Pinto.

The money was paid to the court and destined for the public coffers.

'Account' in the judiciary

Another noteworthy point in the case is the way in which the petition of the slave incurred costs in the Courts of the then District of São João da Palma, referred to in the document as a 'bill'.

Paula was charged for the “records”, “term of view”, “said”, “conclusion”, “publication”, “seal”, “reply of the Prosecutor” and “definitive”, among others, with amounts ranging from $240 to $2000, according to the figures of the time.

The process totaled 6,240 réis. The list with the bill, described in the lawsuit, highlighted “Slave Money found in Court”, i.e. it had been paid by her.

Return to the past

There are many doubts about the story of Paula, especially about how she managed to get the money to pay for her freedom, considering the difficulties that the enslaved faced at the time.

Perhaps this doubt will never be solved, but as historian and professor at the Federal University of the state of Tocantins (UFT) Rita de Cássia Guimarães Melo explains, the enslaved managed to join together some change in different ways.

“It may be that she managed to accumulate what is called a peculium, a small peculium. It could be that she was a talented person, who provided good services, so she was always given some kind of money, some kind of material good, so it was very common for them to get it. Many slaves only achieved their freedom by buying their freedom from their masters,” said Rita.

The historical context of the time can also lead us to understand that the heirs of Bento Rodrigues Lourenço, who remained with Paula after the death of her father, may have accepted freedom for various reasons, including “advanced age and visible illness”, as one of the documents addressed to the judge of orphans says.

“You don't want an enslaved person because you can't enslave a sick person. They no longer fulfill the role of working, so these old slaves were discarded,” the historian recalled, citing the Sexagenarians Law (1885) which caused the abandonment of people over 60 who could no longer be owned by their masters.

In addition, there is also the factor that, with the hard work that enslaved people were generally subjected to, it was not common for black people who lived in these conditions to reach the age of 60.

“The average lifespan was very short. So let's say she was perhaps 40, then she would be considered old because she no longer procreated, she no longer had the same strength or she had already had many children. Remember that women in this period worked hard. Black women had to carry on the daily lives of the families of their masters, cooking, washing, ironing and looking after children. And even today this is still reflected in the dependence on having someone at home to clean your house,” said Rita, about the historical period in which the slave Paula lived and which has had an impact on the formation of society today.

For the historian, when we think about the state of Tocantins, we think about events since 1988, when the State was created. But there is a lot of history before this period, involving the time of Colony and Empire Brazil, which should not be forgotten.

“There's no escaping this past, 30 years for history is very little. So if we don't recover the history of the state of Tocantins, we'll be talking about this eternal present. A good way of building this past would be to reconstruct the relationship between the north and the south of the state of Goiás and to understand how this region came to be, and how it is today. It's important to have historical documents in the region so that other researchers can also research indigenous history, the history of slavery, quilombos, the way the environment was appropriated. All of this could be researched in this region to make this place better known,” said Rita.

Historical survey continues

Other court documents from the imperial period and other historical moments in the state of Tocantins will be cataloged and made public by the School of the Judiciary. The aim is to provide the population with an understanding of the past. According to Esmat, access to these archives makes it possible to carry out research, studies and debates on the history of the state of Tocantins.

Just like the story of the slave Paula, who gained her freedom after paying for a letter of freedom, many similar stories are recorded in historical documents and stored in the forums and registry offices of the state of Tocantins.

For the historian, these documents are of great importance and need a place to be preserved to facilitate research.

“Esmat is fulfilling this role of organizing these documents, but there are many documents out there that are completely disorganized and many are lost, lost because they are poorly packaged. And when these documents are lost, you lose memory, you lose history, you lose the ability to understand the past. So these documents are extremely important,” said the professor, who has a doctorate in history from USP and a post-doctorate from UFRJ.

To access the original document, click here.

To access the transcription, click here.