They are recognized for their social organization, customs, languages, beliefs and traditions, and their original rights over the lands they occupy, according to the articles 231 and 232 of the Federal Constitution. But in practice, prejudice, threats and situations of disrespect are still part of the reality for the indigenous peoples.

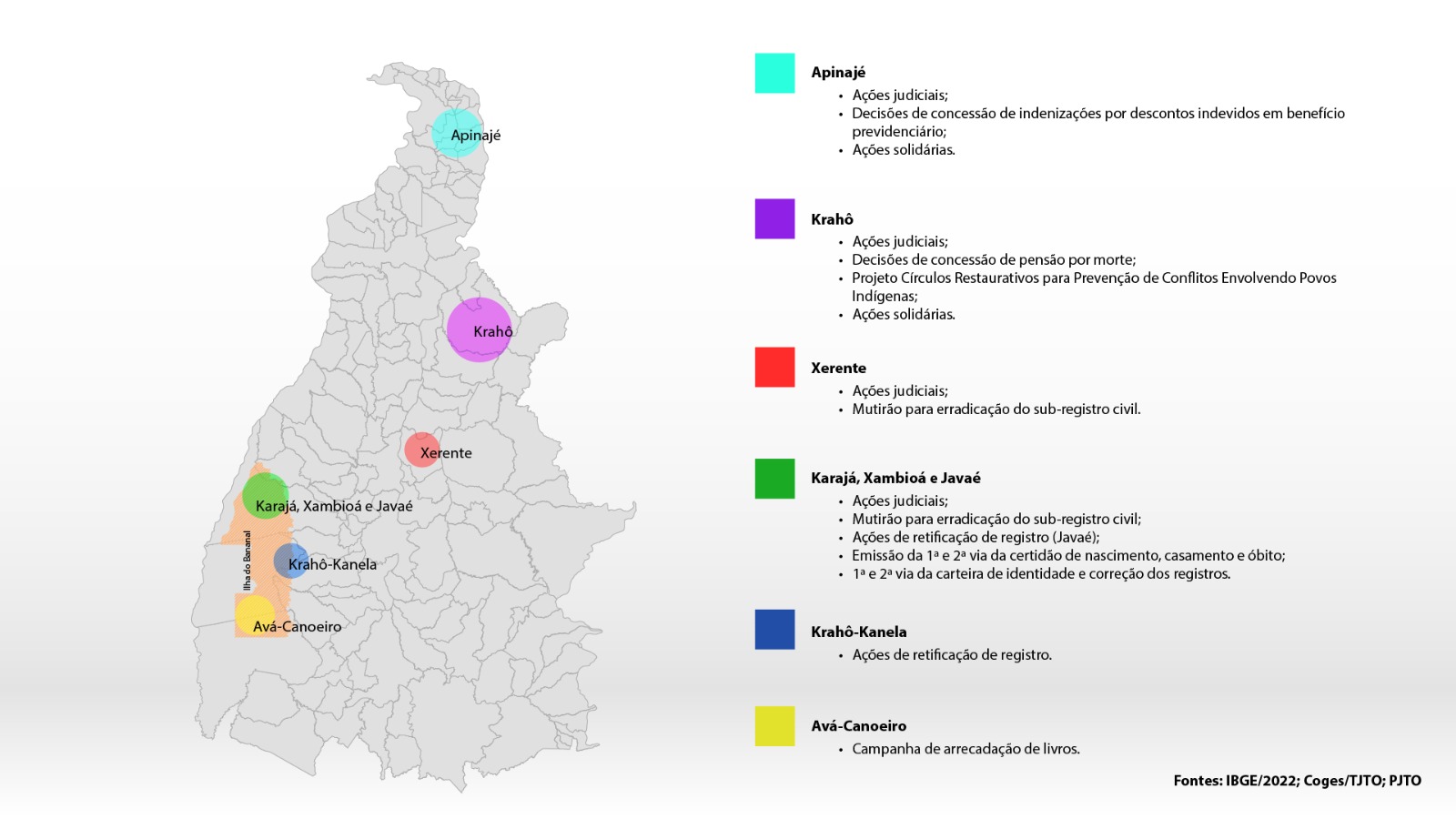

In the State of Tocantins, the Judiciary (PJTO) acts to guarantee the fundamental rights of the indigenous peoples, promoting justice, citizenship and facilitating their access to essential rights. In this sense, on the date that marks Indigenous Peoples Day (April 19th), the Court of Justice of the State of Tocantins is highlighting actions taken to protect and include the ethnic groups that live in the State of Tocantins.

Indigenous citizens and the judiciary of the state of Tocantins

Karajá, Xambioá, Javaé, Xerente, Krahô, Krahô-Kanela, Apinajé, Avá-Canoeiro and Pankararu. There are nine ethnic groups in the State of Tocantins, represented by around 20,000 people who declare themselves indigenous in the State, according to data from the Census of 2022 by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

They represent 1.32% of the total population of the State of Tocantins and live in different regions of the State, such as: Tocantínia (4,086), Goiatins (2,650), Tocantinópolis (2. 352), Lagoa da Confusão (2,340), Formoso do Araguaia (1,633), Itacajá (1,195), Pium (983), Gurupi (802), Palmas (645) and Maurilândia do Tocantins (483), according to the IBGE.

Just like other citizens of the State of Tocantins, indigenous people can also find in the state judiciary the doors to guarantee rights and citizenship, through justice that is ever closer, more innovative and more effective.

More than 2.5 lawsuits in progress

According to data from the Coordination of Strategic Management, Statistics and Projects (Coges/TJTO), based on lawsuits involving indigenous peoples as parties, there are 2,573 lawsuits in progress in the Judiciary of the State of Tocantins.

The ethnic group with the highest number of cases is the Xerente, with 996; followed by the Krahô (841); Karajá (424); Javaé (187) and Apinajé (125). Many of the cases refer to crimes committed against indigenous people and their culture, as well as rectification or supply, or restoration of civil registration, and birth registration after the legal deadline.

The counties with the most cases in progress are: Cristalândia, Formoso do Araguaia, Goiatins, Itacajá, Miracema do Tocantins, Palmas and Tocantinópolis.

Justice closer to native peoples

Bringing the Judiciary of the State of Tocantins closer to the indigenous peoples also requires moving personnel and physical structures to the communities. This action takes the form of the "Restorative Circles for the Prevention of Conflicts Involving Indigenous Peoples" Project.

The initiative of the Judicial Center for Conflict Resolution and Citizenship (Cejusc) in the District of Guaraí, in partnership with the Cejusc in the District of Itacajá and the Permanent Center for Consensual Methods of Conflict Resolution (Nupemec), works to reduce any distance between the Judiciary and indigenous peoples.

The project arose from the difficulties of the indigenous people in dealing with money (poré in the Krahô language). The vast majority are in debt and, as a guarantee of credit, many have ended up handing over their debit and credit cards to local traders, a situation that has lasted since the 90s. In addition to this problem, the Judiciary team detected other situations of conflict between indigenous people and the non-indigenous community.

To achieve the objectives of the project, the Judiciary of the State of Tocantins is visiting the 41 Krahô villages in the municipalities of Itacajá and Goiatins, in northern Tocantins. The aim is to prevent conflicts through dialog between traders and indigenous people.

The initiative also seeks to encourage indigenous peoples to play a leading role and reduce indebtedness in the communities, as well as implementing the CNJ resolutions 225/2016 and 454/2022, which deal with Restorative Justice and the right of the indigenous peoples to access the Judiciary.

During the visits to the villages, lectures are given on Indigenous Rights, Financial Education and Indigenous Family Farming. By this week, 22 villages had already been visited by the project team.

This month, on the 10th, 11th and 12th the White Water (Água Branca), Taipoca and Kinpojkré villages were visited, all in the municipality of Goiatins. The program was attended by Federal Justice Pedro Felipe Santos, of the Federal Regional Court of the 6th Region; Judge José Maria Lima, a member of the Regional Electoral Court (TRE) and coordinator of the permanent projects; Opttins researcher Marcilene de Assis Alves Araújo; as well as representatives of the Indigenous Missionary Council (Cimi), the City Council of Itacajá and members of the Military Police of the District of Goiatins.

Transforming experience

For those who work to promote justice, such as Judge Luciana Costa Aglantzakis, who is responsible for the District Court of Itacajá and coordinates the project, the experience has been transformative.

The Judiciary could go to all the courts in Brazil and empower the indigenous peoples through the RJ (Restorative Justice), depending on the conflict they are experiencing," says the magistrate, explaining Restorative Justice. "It's a technique for resolving conflicts and Kay Pranis' peace-building circles are a way of bringing empowerment, citizenship, autonomy and dignity to the indigenous peoples.

The project was the highlight of the 3rd Judicial Management Award by Minister Sálvio de Figueiredo Teixeira, held by the General Internal Affairs of Justice of the State of Tocantins (CGJUS) in February this year, during the 3rd Meeting of Permanent Chiefs of Justice and the General Internal Affairs of Justice of the State of Tocantins (Encope).

"Another affirmation of who I am as an indigenous people"

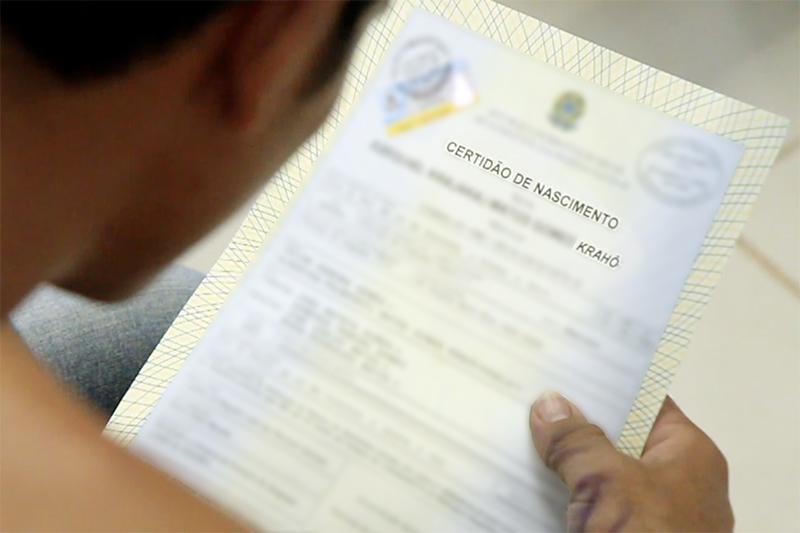

"For me, it was more of an affirmation of who I am as an indigenous people, right? Because I know I'm indigenous, but when I got to a place and presented my document that didn't have an indigenous name, it was like a doubt, right?" says Wagner Katamy Krahô-Kanela, talking about the court decision that guaranteed him the right to sign the name of the ethnic group to which he belongs.

Today, wherever I go, I present my document and say who I am. It's an easier way to introduce myself and say who I am and which people I belong to.

Wagner Krahô-Kanela and several other indigenous people who didn't have an identity had to go to court, through a Public Registry Rectification Action, to get the right to include the name of the ethnic group to which they belong on their birth certificate.

The difficulties they had in proving that they were indigenous, due to the absence of their name on the document, ended up putting their rights at risk. This situation began to change with the decisions of the Judge of the District Court of Cristalância, Wellington Magalhães.

117 registration rectification actions

Like this lawsuit, more than 100 others were filed in the District of Cristalândia between 2015 and 2017. Of the 117 cases distributed in the district during this period, 80 were judged by Judge Wellington Magalhães, all of which were completely well-founded, and 79 of which were decided in less than a year.

During this period, indigenous people from the Krahô-Kanela, Javaé and Ãwa ethnic groups, all located in the Bananal Island region, benefited.

The decisions of the magistrate take into account the principle of the dignity of the human person, in the sense of guaranteeing indigenous people the right to and respect for the preservation of their identity, a fundamental principle of the Democratic State of Law.

"The right to cultural identity is based on the idea of the name as a way of preserving the entire history and background of a given individual. It is therefore a way of confirming the roots and origin of a person. In relation to the indigenous peoples it is no different, the name, here understood as that of indigenous ethnicity, represents an intense connection not only with the roots of their land and territory, but also as a way of identifying their group," says Judge Wellington Magalhães in an excerpt from one of his sentences, referring to an Action for Rectification of Public Registry for Inclusion as Patronymic Name of Indigenous Ethnicity, proposed by Kawã Maukawa Hadomari Javaé.

The Brazilian Constitution is a broad instrument for protecting and safeguarding indigenous rights, insofar as, as the highest law, it ensures that the rights to land, culture and identity, among others, are guaranteed to them.

"I can only thank the Judiciary for its efforts to make a dream of our people come true. The inclusion of my ethnicity on my birth certificate has redeemed my identity and strengthened our culture," said Chief Wagner Javaé, from Boto Velho Village (Old Boto Village).

He thanked Judge Wellington Magalhães for initiating the "dream of social inclusion for all".

Audience by vieoconference

As a means of facilitating indigenous access to justice, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, in June of 2021, the District Court of Cristalândia held a hearing via videoconference with the Karajá of Bananal Island.

At the time, Daniel Ohori Karajá, 67; Iracema Karaja, 82; and Butxiweru Karajá, 77; went to court with requests for late registration of indigenous deaths. With the support of the lawyers of the parties, Judge Wellington Magalhães held the hearing in videoconference format, on the Yalink platform, made available by the Court of Justice of the State of Tocantins, to hear the parties and witnesses in the case.

Justice, inclusion, citizenship and social responsibility

Joana Tepkaprek Krahô and Madalena Krahô, 106 and 104 years old respectively, as well as belonging to the same ethnic group, have similar stories. What they have in common: a court decision that would repair moral and financial damages. The two centenarian indigenous women were denied the right to receive a death pension by the National Social Security Institute (INSS), after decades of living together with their respective partners: Alcides Yaioko Krahô, who died in April of 2018; and Bernardino Krahô, who died in August of 2021.

Even in the face of the pain of losing their partners, the widows Joana and Madalena Krahô had to go to court to get their union and family ties recognized as a couple.

In decisions based on the precepts of social responsibility, inclusion, citizenship and the promotion of justice, Judge Luciana Costa Aglantzakis, head of the 1st Civil Court of the District of Pedro Afonso, in these cases answering for the District of Itacajá, a municipality located 314 kilometers from the city of Palmas, not only recognized the family institution in the two lawsuits, but also granted a pension for the two in the monthly amount of one minimum wage, a right that had been denied by Social Security.

In the case of the widow Joana Tepkaprek Krahô, the decision was published on July 27th, 2021, and that of Madalena Krahô on April 18th, 2023.

Guarantee of compensation for undue deductions from social security benefits

The Judiciary of the State of Tocantins has also been guaranteeing indigenous INSS pensioners the right to compensation for undue deductions by financial institutions.

Among the rulings in favor of the indigenous peoples of the State are those of Judge Ariostenis Guimarães Vieira, of the District Court of Tocantinópolis. He granted, for example, a 76-year-old indigenous man from the Apinajé ethnic group, retired by the INSS, the right to compensation of R$10,000 from a financial institution, as reparation for moral and material damages.

The indigenous man, from Cocal Grande Village (Big Cocal Village), in the rural area of the District of Tocantinópolis, north of the State of Tocantins, appealed to the Judiciary after having monthly deductions made from his social security benefit, between April of 2010 and July of 2013, in the amount of R$104.45, referring to a payroll loan equivalent to R$3,290.80.

In the decision, published in June of 2016, the magistrate also ordered the institution to refund the amount of R$8,388.00 to the indigenous man as a double recovery of the amount unduly deducted from the pension of the pensioner.

Judiciary attentive to indigenous causes

Attentive to situations of violation of rights, prejudice and omission, the Judiciary of the State of Tocantins has been working not only to guarantee access to justice of the indigenous peoples. Aware of its role, it has promoted actions of social responsibility in several districts of the State, in order to bring knowledge, protagonism and citizenship to the communities.

Many indigenous people don't even have civil documents that can guarantee access to basic rights, such as education and health care. In this sense, the Judiciary of the State of Tocantins has been working for years to eradicate this problem.

One example of this is the initiative by the TJTO and the General Internal Affairs of Justice, which in 2022 carried out an action at the Canuanã School of Bradesco Foundation, in the District of Formoso do Araguaia, to issue first and second copies of birth, marriage and death certificates, as well as first and second copies of identity cards (RG) and correct records.

Also in this regard, in 2012, approximately 10,000 documents were provided to indigenous people from the State of Tocantins through the Citizenship, Right to Everyone Project, an initiative of the National Council of Justice (CNJ) in partnership with the PJTO. During that year, six joint efforts were held in villages to deliver documents.

Access to reading

In order to promote access to reading and encourage the habit from an early age, the PJTO, through the Superior School of the Judges of the State of Tocantins (Esmat), organized a book collection campaign for the Awã-Canoeiro indigenous village. Thanks to the union of the entire Esmat team, civil servers of the TJTO, course students, library users, family members, friends and the community, around 205 copies of literature books for children were collected.

Solidary action

In the District of Araguaína, a charity drive was held last year to benefit the indigenous communities of the region. On that occasion, clothing, footwear, personal hygiene items, as well as bed and bath products, collected by magistrates, civil servers and outsourced workers from the district, were delivered. The items were received by representatives of the Indigenous Health Support House of the District of Araguaína (Casai) to be sent to the indigenous peoples of the region.

Dialogue, culture and rights

Bringing dialogue closer to the judiciary on the culture, rights and duties of the indigenous peoples. This is the aim of the "Indigenous April", a series of four debates about the culture, customs and traditions of the indigenous peoples. The second interview, mediated by Judge Wellington Magalhães, was made available last Monday (April 15th), and the third and fourth on April 17th and 19th, respectively.

Esmat is also responsible for promoting the webinar on "Citizenship and Justice from the Indigenous Perspective of the State of Tocantins - A Necessary and Lawful Dialogue". The aim of the event is to awaken and strengthen the awareness of magistrates, civil servers and the community about the human rights of the indigenous peoples, as well as to understand the cultural order, their customs and traditions, which includes interviews with specialists and scholars on indigenous issues.

Xerente Demands

With a reservation in the area of jurisdiction of the District Court of Miracema, in the municipality of Tocantínia, the Xerente have a friendly relationship with the Judiciary in the search for a solution to legal claims involving indigenous people. In 2019, for example, Judge André Fernando Gigo Leme Netto, head of the 1st Civil Court and Family Court of the District of Miracema, met with Chiefs, peace councillors, elders, students and Xerente leaders to discuss the culture and judicialization of indigenous claims involving custody, adoption, alimony, recognition of paternity and socio-educational measures.